The campaign stepped up a gear on Saturday with a fundraising dinner graced by a virtuoso performance from Marah Louw, the South African singer and actor who famously sang and danced on stage with Mandela at the 1993 rally in Glasgow’s George Square. She even wore the same dress that she wore that day.

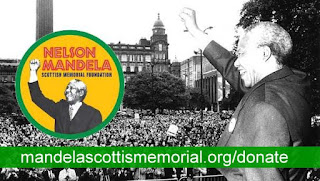

The event included a riveting panel discussion, chaired by journalist David Pratt, who engaged Marah Louw, Deputy High Commissioner Golden Neswisi and Nelson Mandela Scottish Memorial Foundation (NMSMF) chair Brian Filling in sharing their memories of Mandela. The NMSMF, launched last October, aims to build a statue in Glasgow's Nelson Mandela Place.

But the statue is only the start. It will be the focus for a long-term project to ensure that the lessons of the struggle against apartheid remain in the minds of future generations.

The foundation is already commissioning the development and piloting of a course for primary and early secondary pupils on apartheid in South Africa, the life of Mandela, and “its lessons for human rights and challenging racism and on taking action for a better world.”

To borrow the words of Michael McGahey, the campaign will be “a movement not a monument.”

Glasgow was the first in the world to give Mandela the freedom of the city in 1981 while he was imprisoned. That was not won easily, with the Westminster government and many others labelling him as a terrorist.

Brian Filling, who is a long-time anti-apartheid campaigner, recalls that the decision followed years of protests in the city with a flashpoint in 1979 when the Lord Provost invited the South African ambassador to lunch at the city chambers. Campaigners mounted a major protest and catering workers threatened to refuse to prepare food.

Soon afterwards, the Lord Provost was ousted and the Labour Party in the council took the first bold steps towards offering Mandela the freedom of the city.

Eight other UK cities, districts and boroughs followed and a declaration for the release of Mandela eventually won support from 2,500 mayors from 56 countries around the world.

In his speech in Glasgow on October 9 1993, Mandela said: “While we were physically denied our freedom in the country of our birth, a city 6,000 miles away, and as renowned as Glasgow, refused to accept the legitimacy of the apartheid system, and declared us to be free.”

The role of Scotland and Glasgow in the long worldwide campaign against apartheid was further underlined in 1986 when the city renamed St George's Place as Nelson Mandela Place — an important gesture, all the more significant because the South African consulate was based there and it now had the name of its most important political prisoner as its address.

The significance of all this only sank in to many when Mandela chose Glasgow as the place to receive all the “freedoms” after his release from prison. Thousands welcomed him in a torrentially wet George Square.

Two of the many events of that day stood out for me. One was the stroke of luck that got me in the line-up to meet Mandela.

I was soaked from the rain and I’ll never forget his words, full of political significance. “You are very wet,” he said.

He was easy with people. He was tired. But he so wanted to say thank you to the movement that had supported the cause.

The other came as Mandela left the stage later than planned because of his dance with Marah Louw. He came down the scaffolding steps at the back of the platform to a security-controlled empty space in front of the city chambers.

The anthem Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika (God Bless Africa) struck up from behind and, although it was pouring down, Mandela stopped and stood to solitary attention on the stairs. He was getting drenched because the assistant with the brolly was left four steps behind.

I wrote at the time that it was a statement that he was now responsible for a nation as well as a movement.

The only other people watching this were a woman from Namibia, me, and in front of the city chambers a line of Glasgow polis standing to attention and saluting the man.

It said it all about the effect he had. From “terrorist” to man saluted by Glasgow police. How we had moved on. Sadly, how much we still have to move on.

The emergence of a newly confident fascist right makes it all the more important that we ensure future generations know this history and learn from the lessons.

One way to do that is to donate to the Nelson Mandela Scottish Memorial Foundation.

It already has the backing of the last two surviving Rivonia trialists, patrons Denis Goldberg and Andrew Mlangeni, along with South African high commissioner Nomatemba Tambo.

They are joined by Glasgow Lord Provost Eva Bolander and all the surviving “freedom” recipients, Sirs Alex Ferguson, Billy Connolly and Kenny Dalglish and Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden.

You can find out more about the campaign and do your bit by donating at mandelascottishmemorial.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment